On Thursday night a cold front will reach us, bringing strong NW winds to the northern flank of the Alps and temporarily terminating the springlike conditions. Already on Thursday, 28.02, the cold front has announced its approach with intensifying NW winds and slightly decreasing temperatures at intermediate and high altitudes.

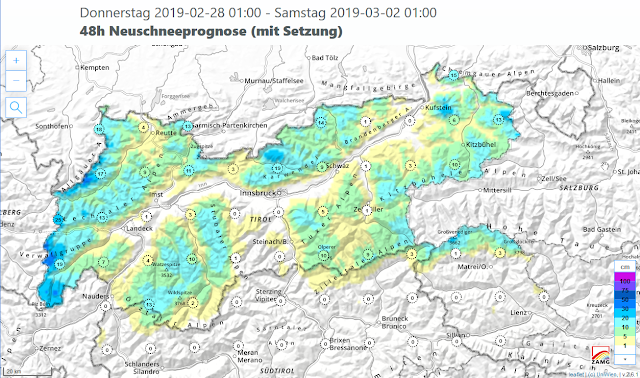

About 20-30 cm of fresh snow is anticipated by Saturday, 2 March, particularly in the northwestern barrier-cloud regions along the Vorarlberg border and in the Karwendel. The snowfall level will initially lie at approximately 1700 m, then descend to nearly 1000 m, according to the ZAMG Weather Service. The cold front will be accompanied by moderate-to-strong velocity northwesterly winds.

The precipitation will initially fall as rain up to intermediate altitudes. On Friday, 1 March, it will create heightened danger of glide-snow avalanches below about 2000 m. In the western parts of North Tirol, avalanche danger level 3 (“considerable”) will be reached. In those regions the first cloudbanks will move in during late evening on 28.02 and impair outgoing radiation of the snowpack, particularly on south-facing slopes which are thoroughly wet. The rain impact will then increase the moisture content of the snowpack and enhance gliding over steep, grass-covered slopes.

Further to the east in North Tirol, the snowpack will generate sufficient outgoing (longwave) radiation until nearly midnight. In addition, there will be less rainfall there. Thus, compared to the western regions, the likelihood of glide-snow avalanches will be less there.

|

| Open glide cracks and a recently released glide-snow avalanche bear witness to intensive snowpack gliding over steep grass-covered slopes, Northern Massif. (photo: 26.02.2019). |

At high altitudes and in high alpine regions, fresh snow and winds will generate the accumulation of fresh snowdrifts, which will then be deposited adjacent to ridgeline slopes and in gullies and bowls. In this connection, the structure of the snowpack is the most important aspect: it is currently quite irregular. This can be evaluated as positive (see Review). The freshly generated snowdrift accumulations are triggerable only in isolated cases, rarely released as avalanches, most likely on very steep, shady, until now wind-protected slopes. There, the old snowpack surface consists of loosely-bonded, faceted, expansively metamorphosed snow crystals in some places.

In East Tirol, the avalanche situation remains predominantly favourable apart from the Main Alpine Ridge. In those regions, the snowpack surface consolidates quite well in the course of nocturnal outgoing radiation. Precipitation hardly exists. Deeply embedded inside the snowpack are isolated trigger-sensitive weak layers which can be triggered by large additional loading on very steep shady slopes at 2000-2600 m. The danger zones occur quite seldom but are very difficult to recognize, unfortunately. Areas where the snow is shallow in extremely steep terrain are the most threatening.

Apart from possible (generally minor) avalanche danger, one needs to give due consideration to the other alpine dangers. Wherever the snowpack was able to freeze during the night, there is acute danger of being forced to take a fall on the hardened snowpack surface on very steep sunny slopes during the early morning hours. This proved fateful for a backcountry tourer on the Reichenspitze on the border of Tirol and Salzburg yesterday, 27.02. On the way from the summit to the ski deposit spot, he took a fall for several hundred meters and lost his life. Caution is also urged towards the cornices which are often vastly overbearing (similar to glide-snow avalanches) in the unpredictability of their threat.

|

| Areas below large cornices need to be critically assessed. Totenfeldscharte, Silvretta. (photo: 27.02.2019). |

As the weekend approaches, weather conditions are improving, according to ZAMG Weather Service forecasts. Winds are shifting to southwesterly, it is turning milder, with foehn influence. Avalanche danger is not expected to change significantly. The snowdrift accumulations at high altitudes will no longer be likely to trigger. The glide-snow activity will recede after the period of precipitation. As a result of higher daytime temperatures and solar radiation, avalanche danger will increase again over the course of the day. In the regions where recent snowfall has been heaviest, numerous relatively small-sized loose-snow avalanches can be expected on extremely steep sunny slopes.

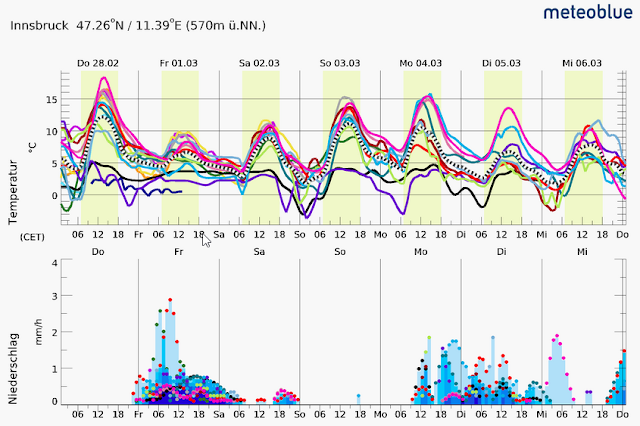

At the beginning of next week variable and instable weather conditions are anticipated. Temperatures will drop once again and a small amount of fresh snow is expected.

|

| Starting at the beginning of next week, skies will be variably cloudy. Temperatures will drop. (©meteoblue). |

Review

Following the precipitationof last Friday, 22.02, conditions have turned springlike again, with mild temperatures and lots of sunshine. the zero-degree level rose to about 3000 m. The avalanche situation was favourable over widespread areas and was subject to the fluctuations of a daytime danger cycle.

|

| Favourable backcountry conditions in recent days were an inspiration for many to leave the office and head into outlying terrain. Sonnblick, Hohe Tauern (photo: 27.02.2019). |

|

| The snow and avalanche situation also permitted steep descents. Haagspitze, Silvretta. (photo: 27.02.2019). |

Due to heavy solar radiation, the snowpack on very steep south-facing slopes is thoroughly wet up to about 3000 m. On north-facing slopes, on the other hand, the snowpack has for the most part remained dry up to 2000 m.

|

| Stability tests have generated only partial fractures at most. The snowpack is well consolidated over widespread areas and quite stable. (photo: 26.02.2019). |

Due to the very dry and clear atmosphere, the snowpack generated adequate outgoing radiation during the nocturnal hours. The wet snowpack surface froze during the night, forming a crust capable of bearing loads. Good quality corn snow was the result in many places. Only in late afternoon did the uppermost layers become thoroughly wet. The wetness of the snowpack occurred relatively slowly, due to the very dry, relatively warm air masses which drew much of the moisture from the snowpack. Thereby, the snowpack also forfeited some of its mass, since the water bonded as condensed water inside the snow crystals was “sucked up” by the air, in effect.

|

| Corn snow in far-reaching parts of Tirol, such as here on the Freihut in the northern Stubai Alps. (photo: 26.02.2019). |

Gliding-snow activity is generally subject to daytime fluctuations. Glide-snow avalanches have been observed in late afternoon as well as during the evening and in nocturnal hours. This in all probability has to do with the delayed penetration of water into the snowpack down to the lowermost ground-level layers.

|

| Glide cracks and a convex snowpack surface are indicators of snow-gliding. Grieskopf, western Verwall Massif (photo: 27.02.2019). |

|

| Fracture areas of a glide-snow avalanche on Malgrübler, western Tux Alps (photo: 24.02.2019). |

|

| Deposit of a glide-snow avalanche in the Silvretta (photo: 27.02.2019). |

Solar radiation, wind influence, wet loose-snow avalanches from steep, rocky terrain as well as people-and-animals have all had enormous impact in the current snowpack surface. From place to place, the impact is irregular to inhomogenous. This places the snowpack surface in a very good position for coming snowfall: fresh snowdrifts triggerable only over very limited spaces, if at all.

|

| Heavily wind-impacted snowpack surface on the Grossen Wilden in the Allgäu Alps. (photo: 24.02.2019). |

|

| Ski tracks ‘worked on’ by the wind in Kühtai. (photo: 24.02.2019). |

|

| A corn-snow mirror was observed in many places over recent days. Jamtal, Silvretta. (photo: 26.02.2019). |